Although the database of Lancashire Cotton Famine poetry is yet to be populated, I thought I might give you a flavour of the kind of text we have been discovering in our research. The following poems were found during one of our digital trawls by a student intern, Francesca Hayward, who worked on the project last year:

The Blackburn Standard (Blackburn, England), Wednesday, October 15, 1862; Issue 1446. British Library Newspapers, Part II: 1800-1900.

‘America’

I.

O Prince of Peace! how long, how long

Shall sin assert its pow’r,

And war its thousands brave and strong

In distant lands devour?

II.

For men at strife, O Lord, we pray,

Oh bid their contests cease;

Bid angry passions pass away,

And yield to thoughts of peace.

III.

No foreign hosts invade their soil,

No savage hordes they see!

Ready their sacred homes to spoil,

And crush their liberty.

IV.

But ’tis a fratricidal strife

Which angry brethren wage;

A brother takes a brother’s life,

And sons with sires engage.

V.

O Prince of Peace, but speak the word,

And man on slaughter bent

Will quickly sheath the blood-stain’d sword,

A humble penitent.

VI.

Why should the labour of the loom

So long suspended be?

And why should want o’erspread with gloom

The seats of industry?

VII.

Prosperity, O Lord, restore

To thousands in distress;

With peace and plenty evermore

All nations deign to bless.

VIII.

And in their midst, O Lord, be thou

All potentates above;

The Lord to whom all knees shall bow,

The God of peace and love.

September 1862. J.R.

The Blackburn Standard (Blackburn, England), Wednesday, November 26, 1862; Issue 1452. British Library Newspapers, Part II: 1800-1900.

‘The Lancashire Operatives’ Appeal’

By William Eaton.

Pray help us, we are starving;

None can our sufferings tell,

God only knows the anguish

That in our hearts doth dwell.

Pray help us, we are starving;

And cannot work obtain;

To go about a begging

Runs sore against the grain.

Pray help us, we are starving;

This we could bear alone,

But wives and children clemming

Would rend a heart of stone.

Pray help us, we are starving;

Our chattels one by one

We’ve had to sell to buy us food,

And now the last is gone.

Pray help us, we are starving;

Bare boards are our best beds,

And thankful are, if we on straw

Can rest our weary heads.

Pray help us, we are starving;

Home drives us to despair;

No cheerful voices greet us

When we now enter there.

Pray help us, we are starving;

To our country we apply,

She promptly must support us,

Or we shall droop and die.

Pray help us, we are starving;

Pray help us in our need;

Pray help us now and freely

And God will bless the deed.

Horwich, Nov., 1862.

The first poem is a fascinating example where a Lancashire writer addresses the cause of the Famine in the American Civil War. The language is slightly elevated, and the stanzas are numbered, as though they are ‘cantos’ rather than verses. This separates them and suggests that they in some sense stand in their own right. Despite these nods to high culture, the poem’s rhythm is actually ballad meter (four beats / three beats / four beats / three beats, or, to get technical, iambic tetrameter alternated with iambic trimeter), which is actually a popular form associated with song.

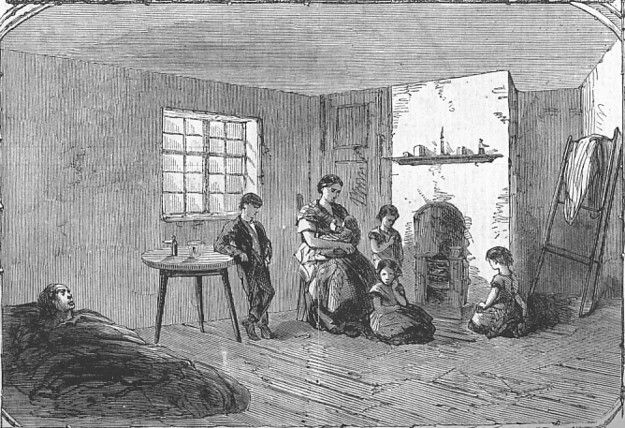

The second poem, ‘The Lancashire Operatives’ Appeal’, assumes a collective voice for Lancashire mill workers. It is an example of the kind of Lancashire Cotton Famine poem which serves as a direct appeal for charity. The style of verse here is simple and might easily be sung. This is down to the repetition of the first line and the easy meter, which is based on iambic trimeter.

Although digital searches proved profitable in the early months of the project we very soon found that we exhausted the newspapers which had been digitised. Vast amounts of newspaper pages remain to be searched and most of these are not held in the British Library but in local libraries across the Lancashire region. Although libraries do a good job in preserving local heritage material, the reality is that these texts are a long way from digitisation (and therefore real preservation) given the amount of funding available to the sector. We feel that, quite apart from our academic interest in these poems, we are helping to highlight the fact that treasures exist all around us, just waiting to be discovered.

Dr Simon Rennie

University of Exeter