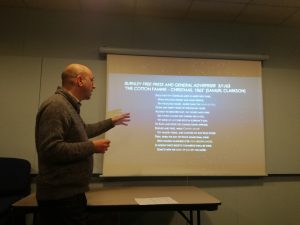

Welcome to the second day of our Cotton Famine Christmas Countdown! To get us in the festive (sort of) spirit, we’re featuring a seasonal Cotton Famine Poem every day in the run up to our special Christmas event with Jennifer Reid on 20th December. Free tickets for the event are available here: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/the-twelve-cotton-famine-poems-of-christmas-tickets-52954230529

Today’s poem is by ‘The Blackburn Poet’ William Billington, and was published in the local newspaper of nearby Accrington, The Accrington Guardian, on September 19th 1862.

COWD WINTER IS COMIN’ WONST MOOR.

(BY W. BILLINGTON.)

It’s wearin’ tort t’ back end o’ t’ year,

Un’t toimes duzend offer to mend,

Bud wossen o’ t’ two, un aw fear

Meh warp’s welly woven to th’ end;

For aw’ve noather money nor meyt,

Nor means to keep want fro meh door;

Thin clooas, un nought gradely to heyt —

Un winter is coming wonst moor.

A werkin mon’s whoam is bud bare,

Uv his werk or his health chance to fail,

For a koite cannud keep up i’ th’ air

When id loyses id streng or id tail.

A twelvemon sin aw wur unshoped,

Un we wor herd howden affoor;

But neaw, when o’ t’ bed clooas is pop’t,

Cowd winter is comin’ wonst moor.

Meh hert jumps for jhoy uv a neet,

When aw stur eawt or step ocross t’way

To see sich o’ childer i’ th’ street

So full o’ thur frolics un play.

God bless ‘em! aw kno, they dornd kno’

Heaw parents ur pincht un heaw poor;

Un id’s wee luz they downd do – for, oh!

Cowd winter is comin’ wonst moor.

“God niver sends meawths witheawt meyt”

A proverb us owd uz id’s true;

Un iv m[?]n oud’nd foe eawt un feyt,

Hands un meawths ud hev plenty to do,

Id’s o’ lung o’ t’ Merrican war

Ut cotton is kept frae eawr shore,

War want still keeps hippin’ uz nar,

Un winter is comin’ wonst moor.

Ther’s chaps wod hez plenty o’ brass

Con heyt, un see honest men clam;

Bud changes may yet come to pass —

Their cake is’nd etten to th’ bem!

For Fortun’s a whirligig witch

Wod sometimes will turn up the poor,

Un deawn into t’ dust wi’ the rich,

Un mek em feel winter wonst moor.

Id’s nonsense to bother un fratch,

Un blame me for singing this song;

For weyn o’ run eawr tether to t’ ratch,

Or shall hev affoor id be long.

There’s theawsands beside me un yo,

Wod wonst hed loife’s blessins in stoor,

Neaw shiverin’ loike sheep among snow,

When winter is comin’ wonst moor.

O! t’ grave is a refuge o’ rest

For us o’ when weyn finish loife’s race!

Bud id dants booath the bravest un best

To reep i’ deeath’s terrible face;

So a let us keep potterin’ on,

Un live tho’ wi loie upo’ t’ floor;

Let’s howd up wur yeds wal wi con

Un face this cowd winter wonst moor.

Commentary

While not exactly a Christmas poem, Billington’s ‘Cowd Winter Is Coming Wonst Moor’ is a reminder that, for some people, the end of the year is to be dreaded rather than eagerly anticipated. The poet explains how the hardships of poverty – hunger and the lack of fuel and warm clothing –were compounded by the harshness of the winter weather. The Cotton Famine is directly referenced in the fourth stanza, but Billington notes that any circumstance that causes a working man to lose his employment could be disastrous, whether that be that a trade downturn or a failure of health.

The use of dialect and metaphors relating to the cotton industry (“Meh warp’s welly woven to th’end”) suggest the poet’s authenticity as a voice of the working man, and indeed Billington had worked in Blackburn’s cotton factories. Professor Paul Salveson, in his thesis on Lancashire dialect literature, sees the poem as a rallying cry to the working classes to find comfort in their unity as the winter threatens to worsen the crisis. However, Salveson also points to the strong sense of social injustice in Billington’s Cotton Famine Poetry, and there is also a sense of real anger towards those who ‘hez plenty o’ brass’ but do not help the poor. The fifth stanza is almost threatening towards the miserly rich as it imagines a world turned upside down, in which they too suffer the vagaries of fortune and are brought low, made like the poor to ‘feel winter wonst moor’. Therefore, though the poem ends with the stoicism and determination characteristic of much Cotton Famine Poetry, this was not a poem that encouraged quiet forbearance among the working classes as the best route to obtaining relief.

Dr Ruth Mather, University of Exeter

A Victorian Christmas Card, from Nova Scotia Archives on flickr.com