It’s the final day of our Christmas Countdown! Our event at Bolton Library is tonight at 6pm, so there’s just about time to register for tickets at https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/the-twelve-cotton-famine-poems-of-christmas-tickets-52954230529. We hope to see some of you there – as well as short talks, Jennifer Reid will perform the poems we’ve showcased over the last twelve days, and of course there’ll be some festive refreshments.

Our twelfth poem is Samuel Clarkson’s ‘The Cotton Famine – Christmas 1862’ from the Burnley Free Press and General Advertiser, March 1st 1863.

THE COTTON FAMINE – CHRISTMAS 1862

England! thy Christmas mirth is mixed with tears,

While pinching penury and want despoil

Ten thousand homes, where dwelt thy sons of toil;

Gone are thrifty fruits of struggling years.

Against the brighter past, thy doubts and fears

See future clouds that darken like a foil;

Yet seeds of joy find root in sorrow’s soil;

To Faith and Hope the coming dawn appears.

Endure and trust, while Charity divine

Thy hungry feeds, and clothes thy shiv’ring poor;

Then, when the day of peace again shall shine

With golden gladness o’er yon western shore,

A nobler thrice bless’d commerce shall be thine,

Stain’d with the guilt of slavery no more.

Manchester, Dec. 22, 1862

This poem is already on our database, with a formal commentary by Simon. However, we thought it was worth including it here as it encapsulates many of the themes of the Christmas poetry we’ve highlighted throughout this Countdown, including Faith, Hope, and Charity, which are personified here tending to the poor, and perhaps restoring some Christmas joy. This poem is also particularly interesting, as Simon has noted, because it explicitly recognises Britain’s role in sustaining slavery through the reliance of the cotton industry on slave-produced raw material. Many poems we have found gloss over this, or celebrate Britain’s abolition of the slave trade without acknowledging the more indirect ways in which the nation supported the practice of slavery elsewhere. When we talk about this project, we often discuss how attitudes to the American Civil War among Lancashire workers were complicated, and, contrary to the popular myth, not all cotton operatives were in support of the North and emancipation. Nonetheless, the rousing end to this poem suggests that eradicating the evils of slavery could be a source of hope for suffering people, a means of restoring the dignity of Lancashire’s “sons of toil”.

We hope you’ve enjoyed these daily updates, and that you’ll join us in 2019 as these Christmas poems and more are released on the database. We’ve been absolutely thrilled by the response to the project in 2018 from all around the world, and would like to thank everyone who has helped us with research, events, and publicity this year. There’s lots more to come in the New Year, but until then we wish you all a very happy festive season!

Dr Ruth Mather, University of Exeter.

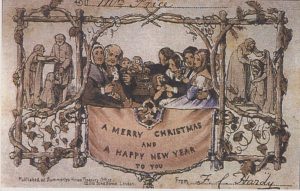

Victorian Christmas card from Wikimedia Commons.